2 September 2025 | Usanas Foundation

Read more on Usanas Foundation

Art, as defined by “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination”, is found in every human society, in every corner of the world. Yet it is not always apparent to us, nor do we all interpret it in the same way. Art is a form of communication that requires our attention and imagination to perceive and truly understand.

Pause for a moment and observe the glowing rectangle in front of you, or in the palm of your hand. You are arguably holding a work of art—a human invention much like the first wheel or weapon, the printing press, or post-it.

This invention operates within a network of networks in both the virtual and physical worlds, without a central point in either one. It conveys a melange of information to us, akin to the frenetic strokes in a Pollock painting that coalesce in the viewer’s eye. Our connection to one another through our art is both our greatest utility and our greatest vulnerability—and it requires our holistic effort to sustain at this moment in time.

Convergence, by Jackson Pollock [1952]

In ancient philosophy, there are two concepts of time: Chronos and Kairos. Chronos is the well-known concept of time we use to measure society on the man-made scale of hours, minutes, and seconds—it exists on a chronological, linear path. In contrast, Kairos is an interconnected moment in time, on an intuitive scale involving the universe. It is often depicted as circular instead of linear, touching our past and future simultaneously in the present moment.

In 2022, a generative artificial intelligence (AI) program called Midjourney began sharing images publicly. The images it generated were designed to be visually appealing to us. Many of them prominently featured a circle, either displayed obviously or subtly behind a canopy of details. These circles appeared consistently, even when the human prompt did not specifically mention them. Midjourney seemed to have identified a theme in the human data it analyzed, or understood our intuitive connection to circles in human society.

Behind the canopy of debate over the pros and cons of artificial intelligence, an AI arms race is unfolding. This race is fueled by human fear and greed, but it can be tempered with our integrity and fortitude.

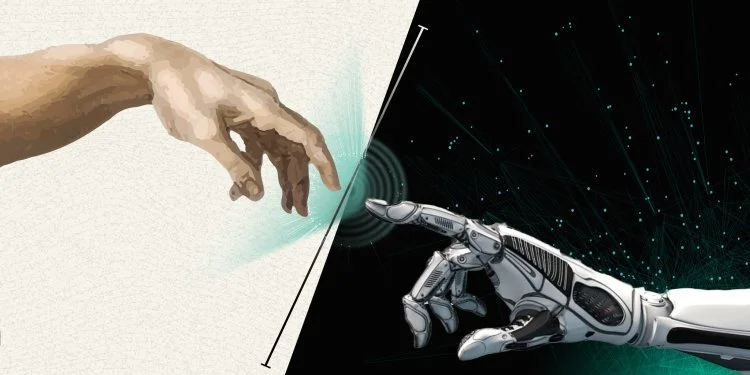

By applying our art to artificial intelligence, we can circumvent world war.

Midjourney prompt: “Circle” [2022]

In some interpretations of the ancient parable of the Tower of Babel, excessive human greed in technology threatens to concentrate power, undermining the inherent diversity and humility of life on Earth.

In a futuristic parable in the same vein, the science fiction masterpiece Dune echoed a warning ahead of its time. Dune is set 10,000 years in the future, in a universe reborn from the ashes of an artificial intelligence apocalypse. As described by the author Frank Herbert, “Once, men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them.” This led to the outlawing of “thinking machines”—a collective term for computers and artificial intelligence in the Dune universe—with an enduring commandment, “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.”

Rewind 10,000 years from this imagined future, then fast-forward from the publication of Dune in 1965 to the year 2020, when artificial intelligence was defined by IBM as the use of “computers and machines to mimic the problem-solving and decision-making capabilities of the human mind.”

An Open Letter: The Pros and Cons of Artificial Intelligence

“I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes,” declared fantasy author Joanna Maciejewska, in a viral post on X.

The debate over the pros and cons of artificial intelligence rage over whether it will support or denigrate human flourishing. Like all human technological advancements in our history, artificial intelligence will displace jobs and impact the global economy. There will inevitably be those who are resistant to such change. But unlike all human technological advancements in our history, we do not fully understand the utility of our invention; we are placing the proverbial cart before the horse. United Airlines was not invented before the Wright Brothers invented the airplane. Game of Thrones was not printed before Gutenberg invented the printing press. Guns were not fired before Wei Boyang invented gunpowder. Industry logically follows invention, not the other way around. The current acceleration of the artificial intelligence industry can be explained by the influence of human fear and greed.

In a 2023 Open Letter published by the Future of Life Institute, more than 30,000 signatories relayed a global message to pause AI development for at least 6 months, citing risks to jobs, proliferation of propaganda, and general loss of control. The signatories included academic researchers, CEOs, and other artificial intelligence experts like Yuval Noah Harari, Elon Musk, and Steve Wozniak. Vice reported how the letter failed to achieve its objective, accusing it of creating “AI hype” and “fear-mongering” to fuel the artificial intelligence industry. Whether or not this outcome was intentional, the letter cited the Asilomar AI Principles, one of the earliest and most influential models for AI governance. The Open Letter explained, “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth, and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

For every pro, there is arguably a con to artificial intelligence, which logically incentivizes the need for its governance. While AI can make everyday life more enjoyable and convenient, it is harming the economic wellbeing of many people and businesses, as well as our environment and natural resources. While AI helps those with disabilities by offering accessibility, it also hurts them by repeating and exacerbating prejudices. While AI makes work easier for students and professionals, it undermines their critical thinking skills.

“Artificial intelligence cheats us, and especially our children, with the promise that our intellectual development will be enhanced when it does the heavy lifting for us,” stated Chris Nadon, visiting professor of political philosophy and humanities at the University of Austin (UATX). “Less obviously, digital technology pushes us to misunderstand education simply as the transfer of information, not, as Plato argued, ‘a turning around of the whole soul.’”

The pros and cons of AI are akin to the good and evil in human nature, as we have created AI in our image. Just as we can exert individual effort to govern our own nature, we can exert holistic effort to govern artificial intelligence.

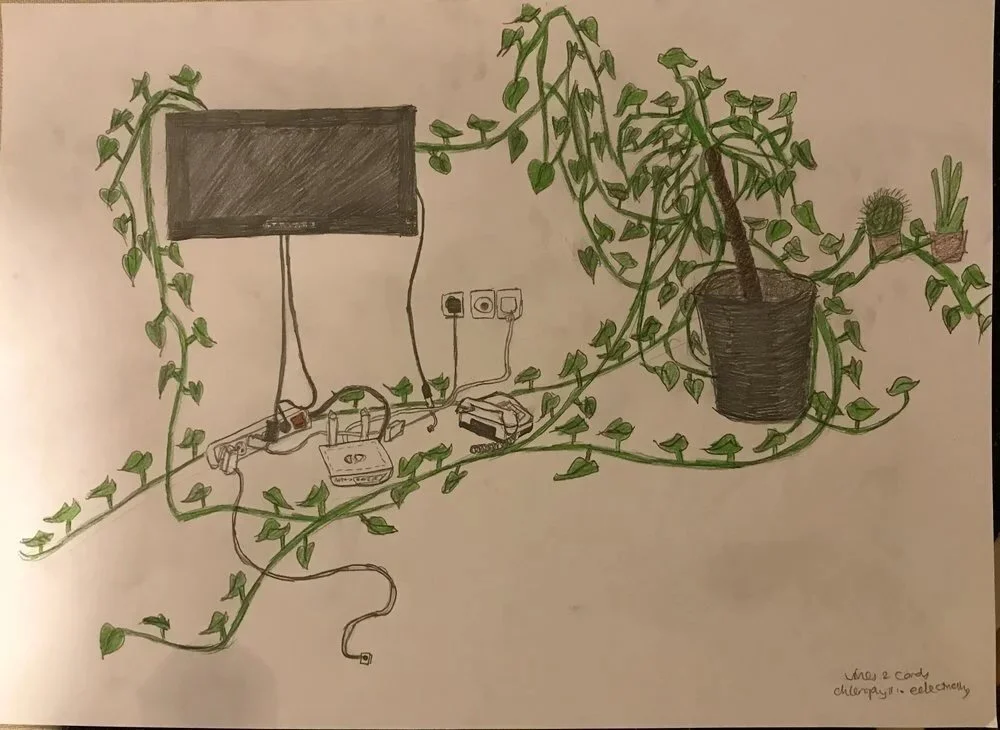

Technology vs Nature

“Every period of human development has had its own particular type of human conflict—its own variety of problem that, apparently, could be settled only by force,” wrote Isaac Asimov in I, Robot. “And each time, frustratingly enough, force never really settled the problem.”

AI does not have the same primary drivers as humans. It does not have a physical body that requires food and sex, nor the social and societal significance that they convey. These drivers are often at the root of human conflict, which would be ceaseless if we ceased to govern ourselves.

Artificial intelligence does require energy, and it is consuming our natural resources at an unprecedented and unsustainable rate. According to a report by the International Energy Agency, the electricity consumption of AI data centers is projected to more than double by 2030. This level of energy consumption would rapidly degrade our environment and human health. Existing AI infrastructure is already accelerating climate change by increasing carbon emissions, which reached their highest recorded levels in 2025. A TIME investigation revealed that nitrogen dioxide concentration levels increased by 79% around a single AI data center. Nitrogen dioxide exposure in humans and animals can cause asthma, respiratory diseases, and even death.

Why is this happening to us and our environment? As early as 2017, an AI arms race was being used to justify efforts by the Trump administration to “invest broadly in military application of AI”. This year, the Trump administration released “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” in accordance with an executive order, “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence.” The administration also began accelerating federal permitting of AI data center infrastructure and rolling back long-standing nuclear safety and regulatory mechanisms. Nuclear development timelines are usually on the order of 10 to 20 years, but the effort to fast-track these timelines to create energy to fuel AI data centers raises serious safety and oversight concerns. As the Partnership for Global Security stated in 2025, “The Trump nuclear executive orders are designed to accelerate (...) an AI wave that is rapidly building into a tsunami.”

Home study: “Vines and cords, chlorophyll and electricity” [2019]

A fast-tracked government approach to AI regulation should not be used for an arms race, but to deter global conflict. In October 2024, media outlets reported that the Chinese government had infiltrated US telecommunications systems in a cyberespionage campaign now known as Salt Typhoon. China was able to infiltrate US systems easily because US infrastructure currently does not allow for real-time responses to cyberattacks, while China’s state infrastructure does. Pipelines, water systems, rail networks, and healthcare industry firms can only report cyber incidents to the US government after they occur. Prior US cybersecurity mandates to address this issue were paused after several states challenged their legality without understanding the context of geopolitical cybersecurity, leaving national infrastructure exposed. A 2025 analysis in Foreign Affairs cited the lack of effective communication between US federal and state representatives and private industries as the cause of the breakdown in protecting US infrastructure.

Anne Neuberger, a former advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technology on the US National Security Council, proposed a deterrence strategy to bridge the cybersecurity gap with China: a digital twin. A digital twin is an AI replica of a physical object, such as infrastructure, that utilizes real-time data and sensors to mimic the behavior and performance of its real-world counterpart. These dynamic models enable private and government organizations to remotely monitor and optimize their physical assets. A digital twin can effectively deter cyberattacks on democratic societies, such as the US.

Renowned physicist, AI researcher and author Max Tegmark warned of mistakes we should avoid when deploying artificial intelligence. These mistakes include turning the discourse into a geopolitical contest between the US and China, and by focusing solely on fear, existential threats, greed and corporate profits. “We have to realize [AI threatens] human disempowerment,” he said. “We all have to unite against these threats.”

The New World Order

“You have to start looking at the world in a new way,” stated Priya Singh, a fictional Indian arms dealer in the film Tenet [2020].

Human history has proven that our inherent impulse is to connect and expand, despite our destructive tendencies. We are a social, cooperative species at heart, which has allowed us to become one of the dominant species on Earth.

As early as 2007, AI scholars warned of an AI arms race that could undermine our collective interest in governance and the application of art to artificial intelligence. In 2009, the International Committee for Robot Arms Control was established out of concern for weapons that can select human targets and kill them without human intervention. In 2016, China questioned the adequacy of existing international law to address the possibility of fully autonomous weapons, becoming the first permanent member of the UN Security Council to state the necessity of developing new international AI regulation. Chinese officials expressed concern that AI could lead to accidental war, especially in the absence of international norms. Over a hundred experts then signed an open letter in 2017 calling on the UN to address the issue of lethal autonomous weapons, and two years later 26 heads of state and 21 Nobel Peace Prize laureates supported a complete ban on autonomous weapons.

“Without entering into a host of doomsday scenarios, it is already clear that the malicious use of AI could undermine trust in institutions, weaken social cohesion, and threaten democracy itself,” declared Secretary-General of the UN António Guterres. In 2021, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted a recommendation on the “Ethics of Artificial Intelligence”, applicable to all member states of UNESCO. Notably, China and Russia, which are largely excluded from Western AI ethics debates, signed on to the principles. Yet in July 2025, the Trump administration decided to withdraw the US from UNESCO, a decision that will take effect in 2026.

Yoshua Bengio, a Canadian computer scientist who was one of the earliest pioneers in developing deep learning, has expressed concerns about the current concentration of power in the AI arms race. He believes that this poses a danger to capitalism and that artificial intelligence tools have the potential to destabilize democracy. Bengio warned about a “conflict between democratic values and the ways these tools are being developed.”

As demonstrated by the Trump administration, the mere possibility of another state gaining commercial or military advantage through artificial intelligence provides strong incentives to cut corners on safety and strategy. This increases the risk of critical failures and unintended consequences, including world war.

Karen Hao, an artificial intelligence expert and investigative journalist, describes in Empire of AI how this AI “arms race” is driven by a “quasi-religious” fanaticism in the tech industry, with an inordinate level of investment and resources channeled into AI products and services without proven value to human society. An MIT report in 2025 found that 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing to deliver revenue acceleration, with the majority delivering no impact on profit and loss at all. Technologist and media founder Ed Zitron echoed dissent in the tech industry in his viral thesis, The Rot Economy, describing how a “growth at all costs” mentality at the expense of human experience leads to a decline in the value of products and services, with AI being a prime example. “The net result of all of this is that it kills innovation. If capital[ism] is not invested in providing a good service, it will never sustain things that are societally useful.”

So how can we make AI useful and profitable for human society? There is an important distinction between replacing human labor and assisting human labor. According to Karen Hao, “If you develop an AI tool that a doctor uses, rather than replacing the doctor, you will actually get better healthcare for patients. You will get better cancer diagnoses. If you develop an AI tool that teachers can use, rather than just an AI tutor that replaces the teacher, your kids will get better educational outcomes.”

Buried in the MIT report is an illuminating diamond in the rough: the few companies that found success with their AI pilots had developed specific applications and clear AI governance guidelines communicated to all involved. This model directs us on the path toward global governance and the strategic application of AI for the benefit of humanity.

To that end, the UN created a Multistakeholder Advisory Body on AI Governance in 2023 to “advance a holistic vision for a globally networked, agile, and flexible approach to governing AI for humanity.” In an unusually timely fashion, the high-level board put out interim recommendations only two months after being established. Although the UN has been criticized for being bureaucratic, leadership and diplomacy in a global forum are essential for AI governance. Critics have also pointed out that the US-led world order under Trump has failed to meaningfully accommodate non-US stakeholders. Doreen Bogdan-Martin, Secretary-General of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), stated this year that “85% of countries don't yet have AI policies or strategies.” Research from the Centre for International Governance Innovation on AI governance concluded that, “to address criticisms of US hegemony in (...) governance, an effective (...) governance model must respond to non-US concerns while upholding the norms and standards rooted in liberal principles.”

In addition to the UN, there are a plethora of governmental and nongovernmental organizations dedicated to governing AI. These include The Council of Europe, The European Union (EU), The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), The Global Partnership on AI, various Technical Safety Standards, AI Safety summits and safety institutes, the Group of Twenty (G20), and Group of Seven (G7). The G7 “Hiroshima AI Process”, was developed at a historically symbolic location, marking the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. We can learn from history: human catastrophe does not have to occur before AI governance.

“Why did the artist fashion thee? For thy sake, o stranger, he placed this warning lesson into the doorway.”—Posidippus of Pella (mid-third century BC) describing a sculpture of Kairos.

Image: Second century BC replica of the Kairos sculpture in Turin's Museo di Arte Greco-Romana.

In The Three-Body Problem, an epic novel written by Chinese author Liu Cixin, Earth in the near future is dominated by both the US and China. Due to the necessity for human survival, there is no longer a traditional hegemony and concentration of global power. The story explores the positive and negative implications of technological progress, pointing out that the only way for humanity to defeat an existential threat is to treat humanity as a whole.

As our art has shown us, through parable, prophecy, and prompt, human unity is necessary at this moment in time. By applying our art to artificial intelligence, we can circumvent world war.

Evin Ashley Erdoğdu is an author, artist, and analyst. She grew up as a US expat in Saudi Arabia and Japan, and has lived and traveled extensively throughout the Asian continent, from Türkiye, Lebanon, and Iraq to Singapore and South Korea. She is a graduate of Boston University where she studied International Relations, and is a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Evin believes in the power of art to transform society and connect people, something she has always tried to integrate into her own work.

Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the author is associated with in a professional or personal capacity.